Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson’s insistence that “We cannot incarcerate our way out of violence” sets the tone for a nationwide debate over law enforcement, decarceration, and public safety, linking local choices to broader claims about mass incarceration and the aims of Democratic policymakers.

Earlier this year, New York politics drew attention with bold, controversial personnel picks tied to dramatic jail reductions, including an advisor who wants to reduce New York’s jail and prison population by 80 percent and another described as a police abolitionist. Those choices signaled a willingness to pursue radical downsizing of detention systems in the name of reform, and the reaction in other cities has been similar. These ideas are no longer marginal in urban policy conversations.

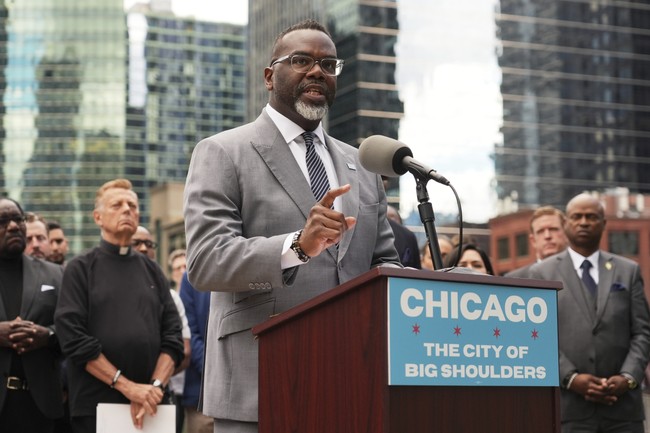

Good luck, NYC. Chicago has its own version of this experiment, led by Mayor Brandon Johnson, who has been clear that he does not believe incarceration will solve violent crime. That position matters because Chicago still struggles with violence, and leadership choices shape whether residents see consequences or relief. The national debate is playing out in city halls and on streets where residents expect protection.

“We cannot incarcerate our way out of violence,” Johsnon said. “We’ve already tried that and we’ve ended up with the largest prison population in the world without solving the problems of crime and violence. The addiction on jails and incarceration in this country? We have moved past that. It is racist, it is immoral, it is unholy, and it is not the way to drive violence down.” The crowd applauded, of course. That applause came from an audience eager for a different approach, but applause is not a policy plan and does not explain how violent offenders are kept off the streets.

Claiming a policy is racist or immoral because it involves incarceration sidesteps the basic fact that accountability matters. Saying many offenders are minorities without calling for higher standards or clearer consequences is what some call the soft bigotry of low expectations. Elected leaders can demand equal accountability across communities while also supporting targeted services, but too often the rhetoric replaces clear enforcement.

Chicago Mayor Brandon Johnson: "We can't jail our way out of vioIence… it's racist" pic.twitter.com/IdroYZaKiG

— End Wokeness (@EndWokeness) November 25, 2025

The numbers speak for themselves when you look at repeat offenders and the concentration of violence in specific neighborhoods. Promises to swap enforcement for social programming require robust, enforceable plans: who delivers treatment, who ensures compliance, and who pays to keep dangerous people away from the public while they get care. Too often elected officials propose expensive alternatives without putting in place the legal or practical mechanisms that make those alternatives work.

That gap between rhetoric and reality benefits no one but the political class that can claim progress without delivering results. Big spending on loosely defined social programs becomes a fiscal windfall for contractors and bureaucracies when success is not measured by reduced victimization. When crime rises, voters pay the price in safety and trust while the political calculations often remain unchanged.

There is a growing body of commentary arguing that the United States is not actually incarcerating too many people relative to the scope of crime, and that simply releasing more offenders will not reduce violence. Here’s more from Heritage:

The idea that the United States is an overly carceral country infected with the scourge of “mass incarceration” is deeply embedded into the mainstream media, academia, and pop culture. But it is just not true, especially taking into account what the phrase actually means in practice and comparing the number of people in prison to the scope and scale of crimes committed. Only a fraction of people who commit crimes are imprisoned—even those who commit violent crimes. Those who support a radical decarceration agenda have gained some headway in their goals by pushing out through various channels the myth that the United States locks up too many people. In reality, the United States likely locks up too few.

Mass incarceration is a myth—and a harmful one at that. Those who push it seek to divide the country on racial lines, all the while ignoring the reality of the scope of violent crime, and what should be done about it. And, ultimately, everyone pays the price.

Practical public safety policy has to include measured use of incarceration for repeat violent offenders alongside proven treatment and reentry programs for those who can be rehabilitated. Locking up those who repeatedly victimize others is not a cruelty, it is protection for communities and a basic obligation of government. When accountability is removed from the toolbox, communities notice in real time.

Ultimately, voters face choices between leaders who offer concrete enforcement strategies and those who prioritize symbolic gestures over outcomes. Cities that refuse to pair supervision and consequence with genuinely scaled and managed alternatives will keep seeing the same hard truths: victims matter, and public safety depends on policies that actually reduce repeat offending rather than just sound compassionate on a stage.