Obamacare didn’t fail; it achieved what its architects intended: reshaping the insurance market and creating political leverage for a move toward government-run healthcare.

I remember the fight over the Affordable Care Act in 2010 like it was yesterday. It was jammed through without a single Republican vote, and many warned then that it was a bait-and-switch designed to reshape the market rather than lower costs. That warning turned out to be less of a cry in the wilderness and more of a forecast.

The law’s architecture forced a transfer of costs and risks in a way that made private coverage unstable for many consumers. Premiums and deductibles rose for healthy, younger people even as subsidies masked true costs for others. That structure created the political space Democrats wanted: a manufactured crisis they could use to push further reforms.

Consider the political timing around subsidies during COVID. Democrats pushed for extensions that conveniently expired at election time, then used the threat of a cliff to frame Republicans as callous. If subsidies were solely about stabilizing the market, why build in a sunset that lines up with elections? The calendar showed strategy more than compassion.

The law also functioned like a nudge toward single-payer, not an accidental detour. It pooled risk in ways that made private insurers vulnerable to adverse selection, and politicians who favor a government takeover openly cheered that outcome. “Despite the fact that Nancy Pelosi said we had to pass the bill to find out what’s in it, the framers of the legislation knew exactly what they were doing,” as critics observed at the time.

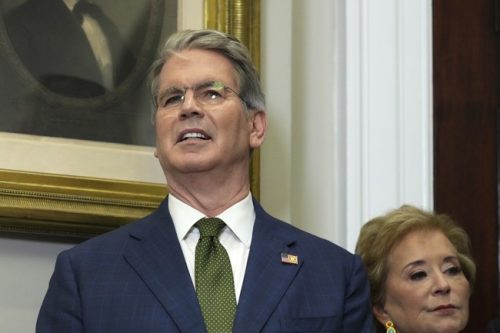

WHAT WENT WRONG WITH OBAMACARE?@Avik: "[Obamacare] overcharged healthy people that needed insurance to help fund the cost of insurance for sick people, and overcharged young people… The end result is, if only sicker and older people buy insurance, the price of insurance for… pic.twitter.com/GYxBdRxXWa

— The Will Cain Show (@WillCainShow) November 11, 2025

Policy thinkers were blunt about the mechanics. Avik Roy warned, “[Obamacare] overcharged healthy people that needed insurance to help fund the cost of insurance for sick people, and overcharged young people… The end result is, if only sicker and older people buy insurance, the price of insurance for everybody goes through the roof.” That’s not a theory; it’s how the incentives played out.

It gets worse when you add the open ambition of prominent Democrats who want to eliminate private insurance. Kamala Harris “said she would abolish private health insurance” in favor of a single-payer system, and other figures on the left have long championed full government control of healthcare. That’s not speculation; it’s a stated political goal.

We are already seeing some of the practical consequences of letting the federal government take on more control: longer waits, higher overall costs, and more one-size-fits-all rules shaped by bureaucracy instead of doctors and patients. Changes labeled “anti-racist” in policy can have real effects on things like transplant lists and triage criteria, and those policy shifts carry human costs. When allocation decisions are driven by ideology and paperwork, outcomes can suffer.

Personal stories drive this point home. An older relative who broke a hip received timely surgery in the current system, but a fully socialized framework raises real questions about who gets prioritized. When resources get stretched and cost-control becomes the dominant factor, older or retired patients are at risk of being deprioritized. Those are the kinds of trade-offs voters deserve to hear plainly about.

Republicans should stop arguing that Obamacare is merely broken and start arguing that it was designed to do what it is doing now. The law’s architects created incentives that destabilized private markets and opened the door to full government takeover. The right response is to put free market alternatives back on the table and let competition bring down costs and improve care.

That means making the case to voters, proposing concrete repeal and replace steps, and restoring patient-centered choices rather than expanding centralized control. If conservatives fail to offer a compelling, market-based vision, the default drift will be toward ever-larger government programs. The stakes are both fiscal and moral: the cost in dollars and the cost in people’s lives when decisions are removed from patients and clinicians.