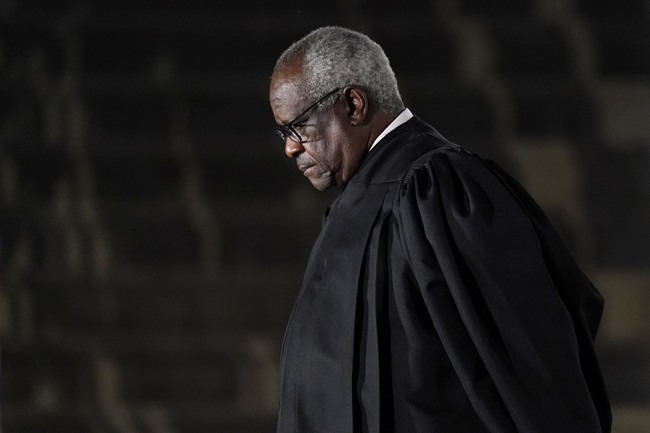

Justice Clarence Thomas sharply criticized the Supreme Court’s decision not to review a military widow’s wrongful death suit, arguing the Court missed a chance to address long-standing precedent that shields the federal government from certain on-duty deaths.

Associate Justice Clarence Thomas issued a pointed rebuke after the Court declined to take up the case of a widow seeking damages for her husband’s death. The suit arose from the 2021 death of Air Force Staff Sgt. Cameron Beck, who was fatally struck while riding his motorcycle after leaving a Missouri military installation. A civilian federal employee, distracted by her phone, collided with Beck as he rode to meet his wife and young child for lunch.

The legal knot centers on Feres v. United States, the 1950s-era precedent that bars many service members and their families from suing the government for injuries or deaths tied to military service. Justice Thomas argued the policy effectively denies meaningful accountability when federal employees cause harm, and he warned lower courts have stretched Feres far beyond any sensible limit. In his view, the Beck matter presented a clear example where ordinary principles of negligence should allow a wrongful death claim to proceed.

Thomas pressed the point that the Court had the chance to correct course and write a new rule on liability, writing, “We should have granted certiorari. Doing so would have provided clarity about [Feres v. United States] to lower courts that have long asked for it,” Thomas wrote. He urged that Feres be revisited and said even if it were left standing the cases that follow it should be narrowed so government actors cannot dodge responsibility simply because the victim served in uniform.

Under Thomas’s framing, Beck’s case would have been straightforward: a distracted driver causes a fatal collision and a grieving spouse seeks compensation through a civil suit. Thomas described the facts as making the wrongful death claim “open and shut,” according to Thomas, yet both the trial court and the court of appeals rejected the widow’s suit. That result, Thomas wrote, illustrates how precedent can produce outcomes that look more like immunity than justice when civilian negligence collides with service members’ lives.

The mechanics of Supreme Court review matter here because four justices must vote to hear a petition for the case to proceed to full briefing and argument. The Court’s denial left the petition unreviewed and the lower courts’ reasoning intact, for now. Justice Sonia Sotomayor, while not joining a grant of certiorari, echoed part of the concern and urged a legislative fix, writing, “I write … to underscore that this important issue deserves further congressional attention, without which Feres will continue to produce deeply unfair results like the one in this case and the others discussed in Justice Thomas’s dissenting opinion,” she wrote.

From a conservative perspective, the denial is frustrating because it leaves a rule on the books that excuses the government from ordinary standards of liability in many cases involving service members. Conservatives who care about accountability for taxpayer actors worry that Feres has morphed into a blanket protection for federal employees at the expense of military families. Thomas’s opinion read like a call for judicial correction: when precedent stands between harmed civilians and justice, the Court should be willing to act rather than preserve a shield for government negligence.

The legal stakes go beyond this single family. If the Justices or Congress move to change the rule, it would open the door to a wave of lawsuits from service members and their families who previously could not seek redress in civil court. Leaving Feres unchanged means district and appellate courts will continue to wrestle with inconsistent interpretations, and families will keep facing an uphill climb when on-duty deaths involve civilian wrongdoing. For now, the denial preserves the status quo and keeps responsibility for reform split between the judiciary’s gatekeepers and the legislative branch.

The Beck case highlights the tension between stare decisis and accountability: a long-standing doctrine can produce outcomes that many find plainly unfair, but uprooting precedent carries institutional consequences. The Court’s decision to pass on review leaves those consequences unresolved and keeps alive the debate over whether the law should favor broad governmental immunity or allow ordinary negligence claims when federal employees harm service members and their loved ones.